Life doesn’t have an alphabet, but two: that of DNA and that of proteins. The genetic code is the Rosetta stone of molecular biology: it lays out how cells convert one alphabet into another — three bases into a single amino acid, but never the reverse. These rules were first summarised in a historic chart (at the time incomplete) by Marshall W. Nirenberg in 1965. This document was key to interpreting the protein-coding portion of the genomes we would start sequencing in a decade.

[This is Episode 2 of A Chronicle of DNA Sequencing through 5 anniversaries (1965-1995), Click me for an overview of the series]

BACKGROUND: A CODE OF THREE LETTERS

The first chart of the genetic code dates 1965, but scientists knew that genetic information is parsed in groups of three bases since December 1961. That’s when Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, Leslie Barnett and R.J. Watts-Tobin published a seminal study on the T4 bacteriophage, a virus of bacteria [1].

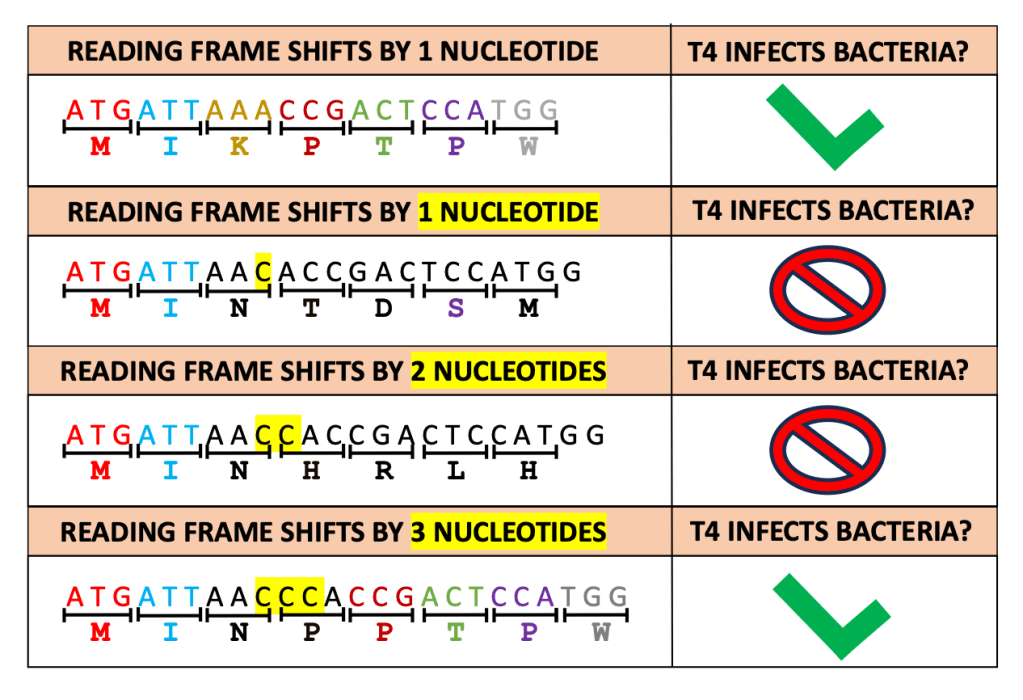

Crick and colleagues found that the T4 bacteriophage could no longer infect cells if 1 or 2 bases were added or removed from its genome, but viruses with three extra or fewer bases were still infectious. They surmised that a change of 1 and 2 bases disrupted the amino acid sequence of a protein essential for infectivity, while changes of 3 bases maintained it. Therefore, they correctly concluded that genes are translated into amino acids in a three-base (triplet) reading frame.

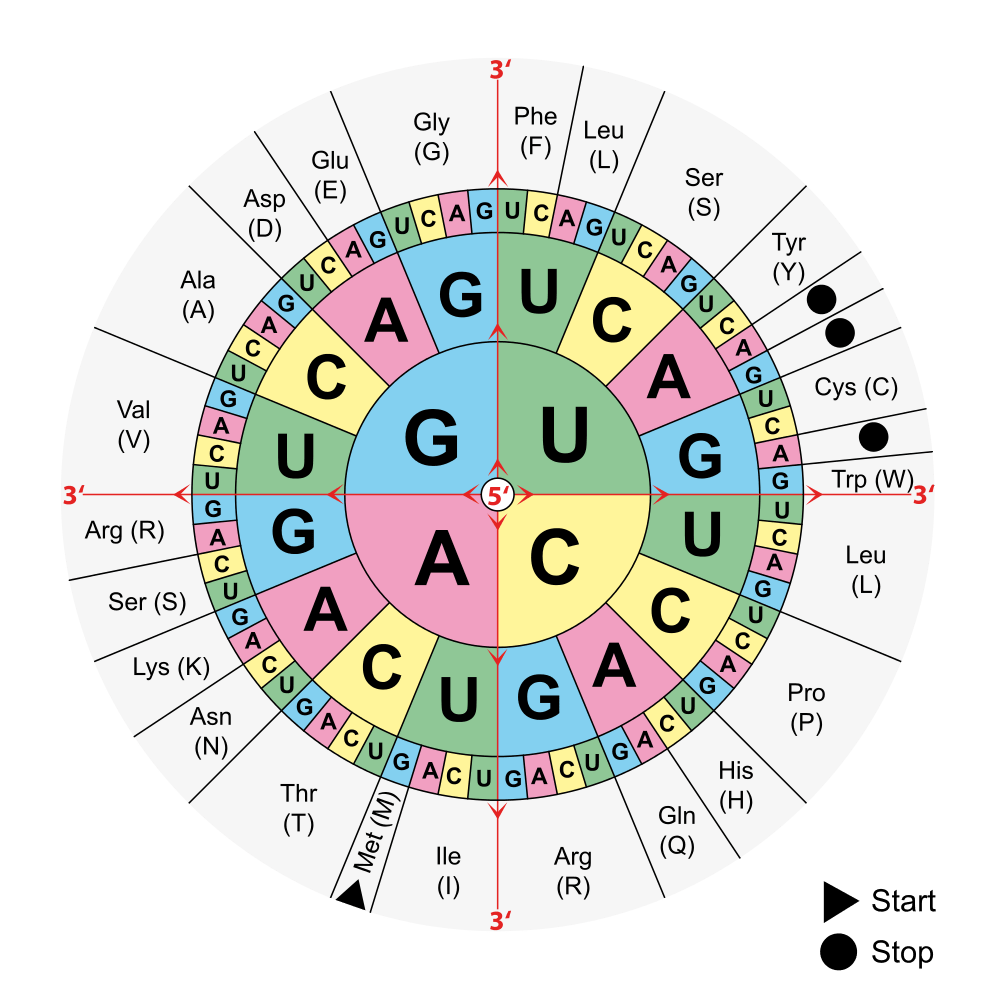

This discovery indicated what a chart of the genetic code must look like: a table with 64 boxes (as there are possible 64 triplets). What scientists had to determine was which amino acids to assign to each box.

Figure 1: The Crick & Brenner experiment (as it is commonly known) in a nutshell

MILESTONE I: DECIPHERING THE GENETIC CODE

In another landmark work, also published in 1961 and known as poly-U experiments [2], Marshall W. Nirenberg and Henrich Matthaei filled the first of the 64 boxes — they just didn’t know yet that the genetic information is organised in triplets. The duo found that an mRNA made of uracil (U) only (the base replacing the thymine found in the DNA) is translated into a protein entirely made of phenylalanine. As the three-base organisation of the genome became clear (a few months after the poly-U experiments), scientists concluded that the UUU triplet codes for phenylalanine.

Nirenberg and Matthaei not only deciphered the first triplet, they also provided a blueprint to fill the other 63 boxes of the chart. And indeed, the race to solve the genetic code was off.

By January 1965, scientists had deciphered over half of the 64 triplets. The boxes in the chart were filling fast, but nobody had systematically tracked this progress. Until Nirenberg himself, by then a star of molecular biology…

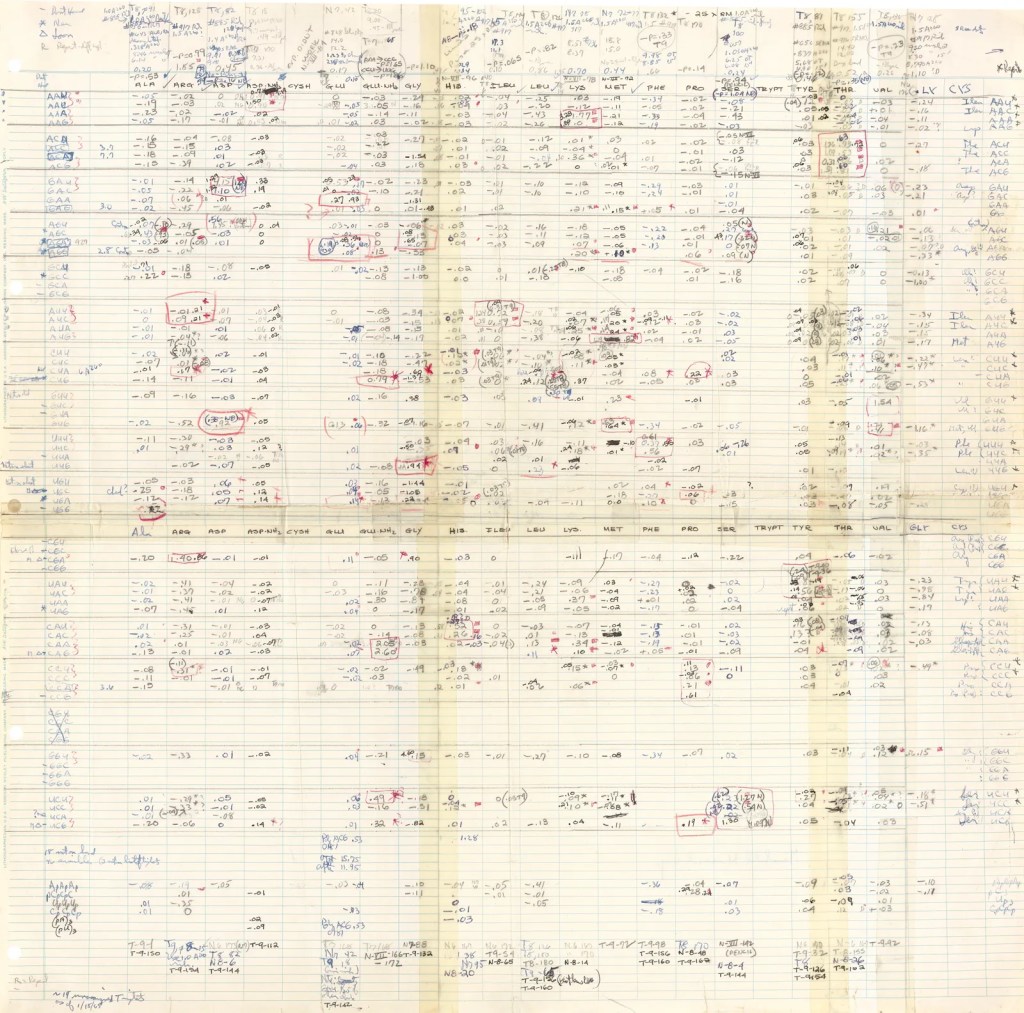

Nirenberg compiled these findings into a single chart — a collection of handwritten papers in pencil, India ink, and multiple ball-point pen inks, all held together by adhesive tape. (Figure 2). Despite its humble appearance, the chart is one of humankind’s most important documents, the Rosetta Stone of molecular biology. This spreadsheet, conserved at the National Library of Medicine (Bethesda), documented our efforts in deciphering the two alphabets of life [3].

Figure 2: The first genetic code, a handwritten chart scattered across multiple sheets of paper (from [3])

AFTERMATH

As scientists deciphered more codons and populated empty boxes, Nirenberg’s team updated the charts with the new findings. We owe most of these discoveries to three teams, those led by Har G. Khorana, Severo Ochoa and Nirenberg himself. But the last box in the chart of the genetic code was filled by the two scientists that opened this story: Brenner and Crick. In 1967, they proved that the last triplet missing, UGA, serves as a stop signal, instructing the ribosome to terminate protein synthesis.

In 1968, Nirenberg and Khorana were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their pivotal role in solving the genetic code. They shared the award with Robert Holley, who had sequenced the first nucleic acid (read more about this discovery in the first episode of this very series).

In the next episode, we will move to 1975 to witness the very first sequencing technology (no, it is not the classical Sanger sequencing many of us have used).

Want to learn more? Please, subscribe to my blog so you won’t miss the next instalment of this series!

Figure 3: The genetic code, from [5]

REFERENCES

- Crick et al. (1961) General Nature of the Genetic Code for Protein. Nature 192, 1227-1232.

- Nirenberg & Matthaei (1961). The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 15;47(10):1588-602.

- Moffatt (2015). Deciphering the Genetic Code: A 50 Year Anniversary. Circulating Now.

- Brenner et al. (1967). UGA: a third nonsense triplet in the genetic code. Nature 4;213(5075):449-50.

- The genetic code, Johson & Wales University.

Leave a reply to A Chronicle of DNA Sequencing in 5 Anniversaries (1965-1995) – WritinGenomics Cancel reply