No, not all exons code for a protein. Far from it.

This week’s post will disprove this common misconception by illustrating three core concepts in genomics Each one is enough to convince you that not every exon codes for a protein. Together, they will reveal a surprising truth: coding exons are a minority, actually.

NOTE: this is the second instalment in my series Common Misconceptions in Genomics. I have already discussed the difference between similarity and homology (episode 1).

THE ORIGIN OF THE CONFUSION

Before we set off, where does this misconception come from?

The confusion about the definition of exon often starts when we first learn about messenger RNA (mRNA). At this point, lectures and books teach us three principles of molecular biology, that we eventually combine in an over-simplified picture. The three principles are:

- Genes are made of exons and introns,

- mRNAs, transcribed from genes, are translated into proteins,

- The spliceosome stitches exons together in the mature mRNA and removes introns.

Feed this info to eager, curious minds and, BAM!, a wrong belief is born: all exons must be protein-coding!

Let’s now dispel this misconception…

CONCEPT 1: mRNAs HAVE UNTRANSLATED EXONS

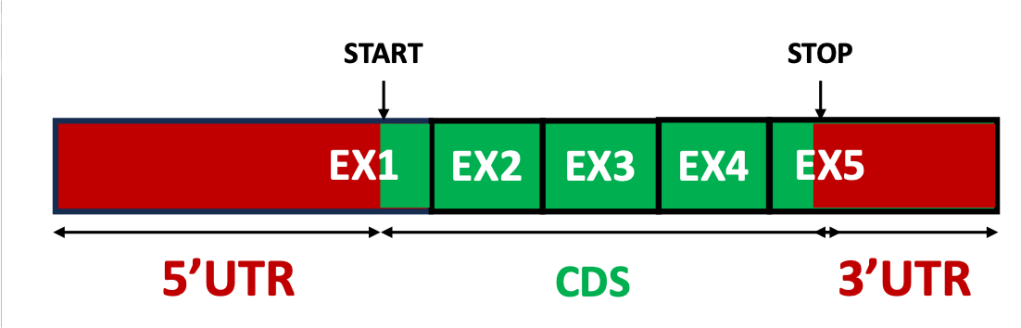

Only a section of the mature mRNA is translated, the coding sequence (CDS). The CDS is sandwiched between two untranslated regions (UTR): the 5’UTR upstream and the 3’UTR downstream (Figure 1). The UTRs range from a few up to thousands of nucleotides in lenght. Importantly, while the 5′ UTR is typically found in the first exon and the 3′ UTR in the last, both can be composed of multiple exons

How abundant are UTR exons? Probably, more than those coding for proteins. In humans, scientists have estimated that there are almost three UTR exons for every protein-coding one [1]. This is a testament to the importance of these untranslated regions, which play a central role in regulating stability, abundance and localization of mRNAs.

Figure 1: The structure of an mRNA.

CONCEPT 2: EXONS CAN ALSO BE INTRONS

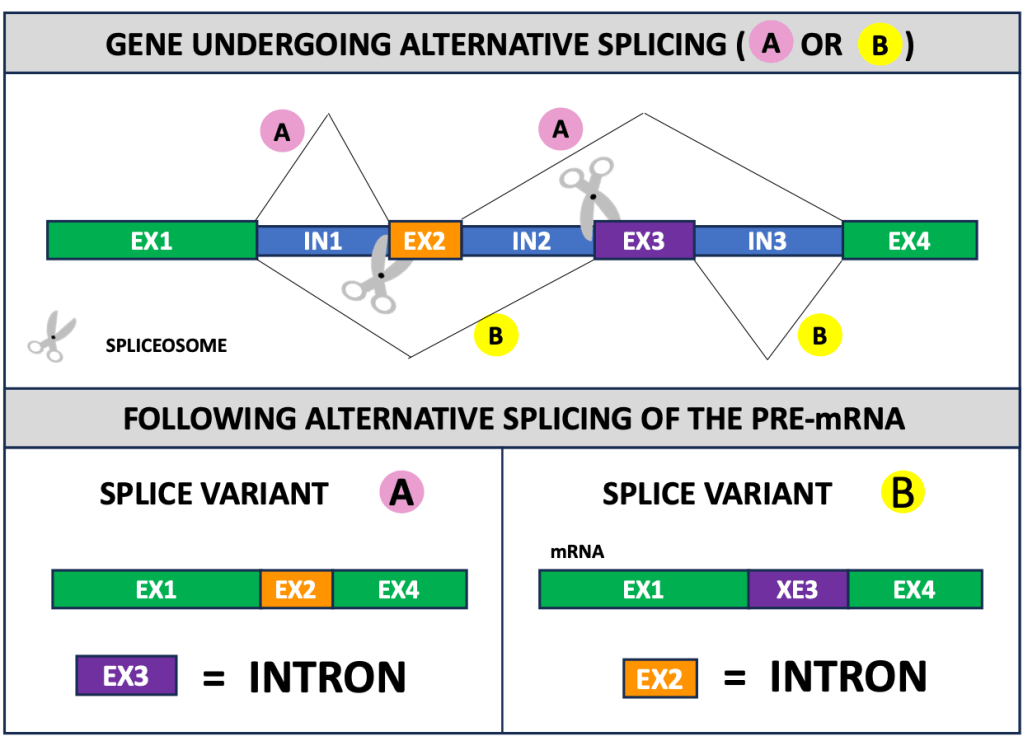

A DNA sequence can be stitched to other exons in a mature mRNA and it can be cut out from another. The two mRNAs, termed splice variants, are generated via alternative splicing, a mechanism that generates multiple combinations of exons from the same gene. This cellular process blurs the boundary between exons and introns (Figure 2): the same sequence can serve as an exon in a splice variant (it will be part of the mature mRNA) and can act as an intron in another one (it will be removed).

How abundant are alternative exons? We are still discovering alternative exons, but this number is high because most genes have 2 or more exons (94% in mice, according to a 2021 study [2]) and mammalian genomes use alternative splicing extensively (up to 95% of their multi-exonic genes undergo alternative splicing [3]). Alternative splicing is essential to increase the repertoire of proteins, expanding the functions that a gene product can serve.

Figure 2: Different exons become introns in distinct splice variants.

CONCEPT 3: NON-CODING RNAs HAVE EXONS TOO

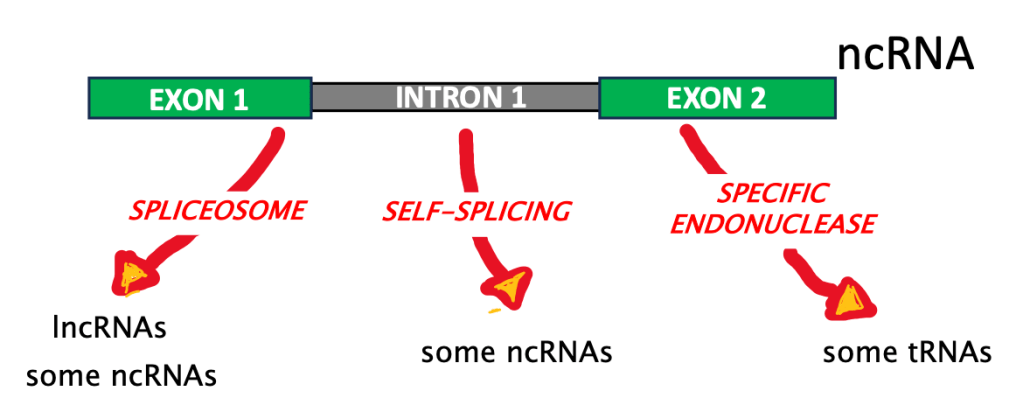

Not every gene is transcribed into a mRNA, and eventually translated into a protein. In fact, cells express a huge number and variety of RNAs that do not code for a protein, the non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). These transcripts often have a modular structure much like mRNAs, with exons and introns. Some ncRNAs, such the long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA), are spliced by the spliceosome (just like protein-coding mRNA!); while others use unique biochemical pathways. This is the case of some transfer RNAs (tRNAs)–we discussed these molecules just last month, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the sequencing of the first nucleic acid!

How abundant are ncRNAs? Our protein-coding genes are an island in an ocean of non-coding DNA: for every nucleotide transcribed in an mRNA, 15 to 45 are transcribed but not translated [4]. The level of transcription for many ncRNAs is weak, but two types of small non-coding RNA, tRNA and rRNA, account for more than 90% of all RNAs in a cell [5]. The primacy of ncRNA is further underscored by the Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): twice as many genes code for ncRNAs (over 43,000) than for proteins (nearly 20,000) [6].

EDIT: interested in the mysterious universe of ncRNAs? Read my series “How many ncRNAs do you know?“

Figure 3: Different pathways are responsible for splicing of ncRNA

SO, WHAT’S AN EXON?

As we have seen, the belief that all exons code for protein is an over-simplification—genomes are much more complicated than this.

Actually, most exons are not coding, because they may

- belong to protein-coding mRNAs but are not translated (the UTRs, reason 1),

- function as introns in splice variants (alternative splicing, reason 2),

- be part of transcripts that do not code for proteins (ncRNA, reason 3).

Year after year, researchers keep unveiling the complexity of our genome. Their discoveries stress the importance of a broader definition of exon, definitely much broader than the one that some of us have acquired at university.

How much broader? Over the next months, we will see instances that challenge the classic concept of exon and intron…

Figure 4: A glimpse in the complexity of our genome

[This is the second “episode” in a series about common misconceptions in biology/genetics. Previously, I discussed the confusing relationship between homology and similarity]

REFERENCES

- Adspen JL et al. Not all exons are protein coding: Addressing a common misconception. Cell Genom. 2023 Apr 12;3(4):100296. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100296.

- Aviiña-Padilla et al. Evolutionary Perspective and Expression Analysis of Intronless Genes Highlight the Conservation of Their Regulatory Role. Front Genet. 2021 Jul 9;12:654256. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.654256.

- Pan Q et al. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008 Dec;40(12):1413-5. doi: 10.1038/ng.259.

- Poliseno L et al. Coding, or non-coding, that is the question. Cell Res 34, 609–629 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-024-00975-8.

- Deng ZL et al. Rapid and accurate identification of ribosomal RNA sequences via deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jun 10;50(10):e60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac112.

- GENCODE Release 48 (accessed June 7, 2025).

Leave a reply to Don’t Confuse Sequencing Coverage and Read Depth [Common Misconceptions in Genomics, EP. 4] – WritinGenomics Cancel reply