The history of DNA sequencing doesn’t start with DNA. No, it starts with another nucleic acid, RNA. An RNA molecule was in fact the first nucleic acid ever sequenced—amid enormous challenges, and 140 kg of yeast.

[This is Episode 1 of A Chronicle of DNA Sequencing through 5 anniversaries (1965-2015), Click me for an overview of the series]

BACKGROUND: WHY RNA, AND NOT DNA?

In the sixties, DNA sequencing faced at least two major obstacles: DNA molecules were just too big (up to hundreds of billions of nucleotides in ten species!) and two different DNA molecules were too similar (long stretches of only four nucleotides) to be separated. Discouraged by these hurdles, scientists turned their sequencing efforts to RNA, another nucleic acid essential for all life. A particular type of RNA, the transfer RNA (tRNA), was particularly amenable to sequencing for three reasons:

- tRNAs were the shortest nucleic acid known at the time, just 70 to 90 nucleotides long, much shorter than DNA molecules.

- Different tRNAs (organisms possess 40 to 60 types) sport distinct sets of modified nucleotides, and these modifications made them easier to purify and separate,

- tRNAs were relatively abundant in cells, which allowed to obtain larger quantities for analysis.

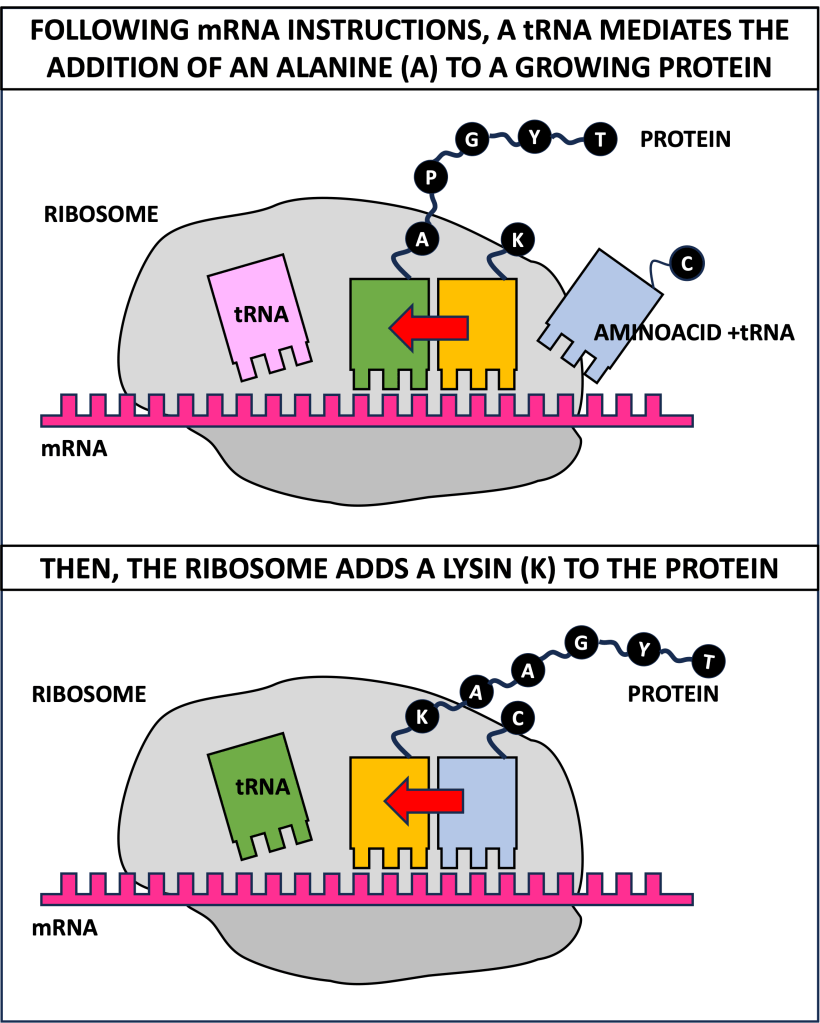

Don’t assume that focusing on tRNAs was merely a plan B, though. Far from it. These molecules play a crucial role in protein synthesis – tRNAs translate the messages encoded in mRNAs into proteins at the ribosomes (Figure 1) – a fact researchers had known since the fifties [1, 2]. They just didn’t know how, and they believed that resolving the sequence of tRNAs held a clue.

[Want to read more about tRNAs? Click me!]

Figure 1: The role of tRNA in protein synthesis

MILESTONE I: SEQUENCING ALANINE tRNA

The first tRNA, and first nucleic acid, to be sequenced was the alanine tRNA of yeast, which mediates the addition of alanine to proteins. Robert Holley and his team, at Cornell University in New York, solved its 77-nucleotide sequence in 1965 [3].

First, Holley and his team developed a method to purify tRNAs from yeast. Holley later admitted that they had no certainty about the purity of their samples, they had to gamble that the alanine tRNA was pure. Had they been wrong, their work would have failed [4]. Fortunately, they were right.

This is an overview of the ingenious, meticulous strategy that revealed the sequence of alanine tRNA [3]:

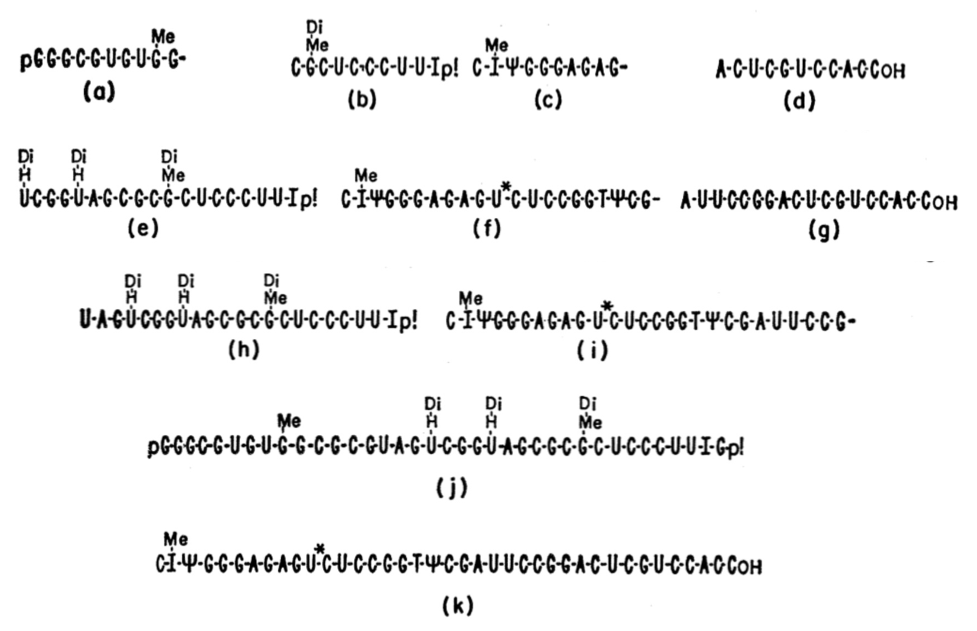

- Scientists broke the tRNA into smaller fragments using the Takadiastase ribonuclease T1 (it cuts after G, and I, a modified nucleotide) and the pancreatic ribonuclease (it cuts after C and U). By controlling how thorough the cutting was, scientists were able to generate overlapping fragments (Figure 2). This overlap was crucial, as we will in point 5;

- The fragments were purified by size and electric charge using chromatography and paper electrophoresis, methods allowing to separate molecules based on their chemical and physical properties;

- Purified tRNA fragments were further cut into single nucleotides or pairs of nucleotides using a combination of enzymatic cutting with the snake venom phosphodiesterase (it cuts from one end of the nucleic acid and progressively move inwards) and chemical digestion (all nucleotide bonds are broken at once)

- Single nucleotides were identified by spectroscopy, based on the unique way each nucleotide absorbs ultraviolet (UV) light;

- Finally, scientists combined the sequences of the fragments into a single molecule. Resolving the sequence of the overlaps (point 1) allowed them to stitch fragments in the right order.

As you may have already suspected, solving the sequence of the alanine tRNA was a Herculean feat. It took Holley and his team 2.5 years, and required the sequencing of 1 g of alanine tRNA from 140 kg (308 lbs) of yeast [5]!

Figure 2: Larger overlapping fragments (Adapted from [3])

MILESTONE II: STRUCTURE OF tRNAs

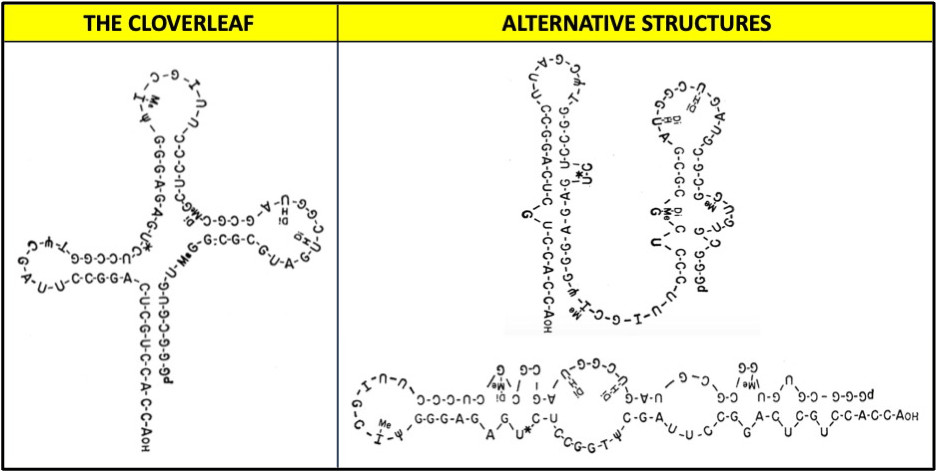

The sequence of a biomolecule such as a tRNA is a window into its folding and the secondary structure it acquires. In turn, its secondary structure holds insights into its function. As such, Holley pondered about the 2D structure of alanine tRNA, in the belief that it could shine light on how protein synthesis works.

Along with his team, Holley proposed three hypothetical structures (Figure 3) [3]. The folding was suggested based on Watson-Crick base pairings (A pairs with T/U, C with G). Of these, one turned out to be the structure that all tRNAs adopt: the cloverleaf. It was suggested by a coworker, Elizabeth Beach Keller, in a Christmas Card. Keller deduced the structure by tinkering with pipe cleaners, paper and velcro [6].

Figure 3: The 2D structures proposed (Adapted from [3])

AFTERMATH

Following Holley’s success, scientists applied to DNA molecules his sequencing strategy, but the method was not powerful enough to sequence a gene. The first reliable, efficient technology to sequence a DNA molecule will arrive only in 1975, thanks to Frederick Sanger and Alan Coulson (the subject of the 3rd episode of this series: 1975 — Learning to Sequence DNA) However, this work highlighted how the sequencing of overlapping fragments could be used to decode the sequence of much longer molecules. This observation will become crucial for shotgun sequencing, which will discuss in the 5h episode of this series (1995 — The Dawn of the Genomic Era).

The sequencing of tRNAs was a monumental step forward in understanding protein synthesis. For this achievement, Holley was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1968. He shared the award with Marshall W. Nirenberg and Har G. Khorana.

In the next episode, we will remain in 1965 to see how Nirenberg wrote one of mankind’s most important documents: the genetic code.

REFERENCES

- Hoagland MB et al.. A soluble ribonucleic acid intermediate in protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1958 Mar;231(1):241-57.

- Zachau HG et al. Isolation Of Adenosine Amino Acid Esters From A Ribonuclease Digest Of Soluble, Liver Ribonucleic Acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1958 Sep 15;44(9):885-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.9.885.

- Holley et al. Structure of a Ribonucleic Acid. Science. 1965 Mar 19;147(3664):1462-5. doi: 10.1126/science.147.3664.1462.

- Holley, R. W. (1968). The Nucleotide Sequence of a Nucleic Acid. Nobel Lecture.

- Kresge N et al. The Purification and Sequencing of Alanine Transfer Ribonucleic Acid: the Work of Robert W. Holley. J Biol Chem. 2006 Feb 17;281(7):e7-9.

- Dr. Elizabeth Keller, 79, Dies; Biochemist Helped RNA Study. New York Times. 1997 Dec 28.

- Hutchison CA 3rd. DNA sequencing: bench to bedside and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(18):6227-37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm688.

Leave a reply to 1965 — Deciphering the Code of Life [A Chronicle of DNA Sequencing, EP2] – WritinGenomics Cancel reply