This is a paradox of rare diseases: they are gaining more and more attention, and yet, a big misunderstanding still surrounds many of them. These misunderstood diseases, known as monogenic disorders, are the ones caused by mutations in a single gene. Clarifying this confusion is crucial for patients, their families, clinicians, researchers and the general public.

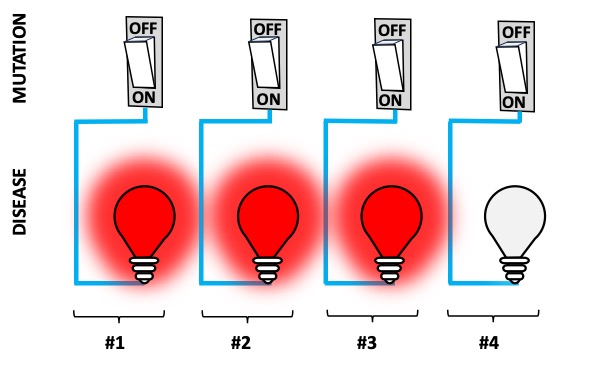

The misunderstanding is easy to point out, but profound: we often mistake “monogenic” with “simple“, “straightforward”, in contrast to polygenic disorders—diseases caused by many genes—which are, instead, considered complex. For monogenic disorders, we expect that if you have a mutation (carrier) disrupting a gene, then you will always be ill. The reality is much more nuanced; genetic mutations don’t work like ON/OFF (ill/healthy) switches (Figure 1). Even in siblings, the same catastrophic mutation can have different outcomes on their health. Just how much different can they be?

To answer this question, I will describe three key genetic mechanisms common to most monogenic disorders. Individually, each one makes a “simple” and “straightforward” disease into a “complex” and “unpredictable” one:

1. Incomplete penetrance,

2. Variable expressivity,

3. Pleiotropy.

But first, why do these mechanisms matter?

Figure 1. How disease-causing mutations DO NOT work: a disease-causing mutation is present (the switch is ON) and so is the disease (red alert).

THE IMPORTANCE OF “COMPLEX” MONOGENIC DISORDERS

Over 71% of all rare diseases are genetic [1], and they are often caused by mutations in a single gene. As a rare disease affects one out of several thousand individuals [2] , not many people live with one specific monogenic disorder. But here is the catch: there are three times more monogenic disorders than stars you can see with your naked eye [3]! To date, scientists have identified over 6,500 of these disorders [4].

As such, collectively, monogenic disorders affect hundreds of millions [5]. For most of these rare diseases, incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity and pleiotropy make the consequences of a mutation hard to predict. They complicate diagnosis, counselling, treatment and development of new therapies.

Understanding how the same mutation can lead to different outcomes across individuals is crucial to improving healthcare of millions of patients and their families.

GENETIC MECHANISMS OF COMPLEXITY

1 – INCOMPLETE PENETRANCE

A mutation shows incomplete penetrance when it causes a disorder in some carriers but leaves others asymptomatic.

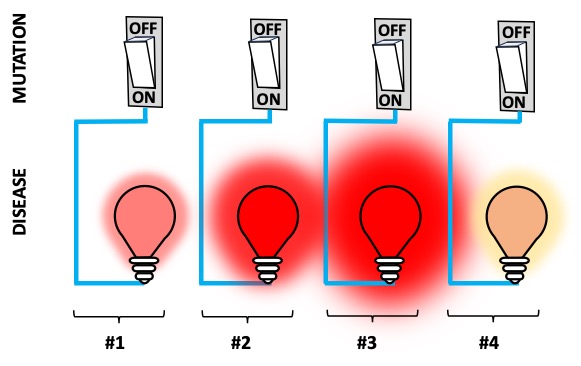

Penetrance is the proportion of those carrying a certain mutation that display the disorder. If all carriers develop the disease, then the mutation is fully penetrant, otherwise the mutation has incomplete penetrance (Figure 2). Penetrance often increases with age: some rare diseases are not apparent at birth, but they develop progressively over childhood and even adulthood.

Figure 2. Incomplete penetrance: a mutation turns the red alert ON only in 75% of the bulbs (only 75% of mutation carriers become sick).

Different mutations within the same gene may have different penetrance. Take the case of cystic fibrosis, a rare disorder that primarily affects the lungs. This disorder is caused by mutations in the gene CFTR, but not all mutations are equal. In 2020, researchers determined the penetrance of 15 mutations in CTFR in the French population [6]: only 3 were fully penetrant (all carriers had cystic fibrosis), while the other 12 had a penetrance ranging from around 2% up to 71%.

Penetrance is a crucial metric in genetic counselling: it represents the probability of developing a disease if a mutation associated with the disorder is present. Imagine a healthy individual discovering that they carry a disease-causing mutation with an 80% penetrance. Their chances of eventually getting sick are 4 out of 5. With this daunting knowledge, they can make more informed decisions on their future, from changes in lifestyle and proactive treatments to psychological support, and family planning.

2 – VARIABLE EXPRESSIVITY

In variable expressivity, a mutation causes a disorder that varies in severity, and sometimes even in symptoms, among carriers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Variable expressivity: a mutation turns the red alert ON in all bulbs, but light intensity varies across them (the disease is more severe in some people than in others).

Variable expressivity refers to differences among individuals with the same mutation. Mutations at different positions along a gene can also result in a single rare disorder with varying degrees of severity, different symptoms, and even diseases. This mechanism is named allelic heterogeneity.

Variable expressivity (and allelic heterogeneity) makes a diagnosis more challenging because symptoms may overlap with those of other disorders. This confusion may result in misdiagnosis and/or in a delayed diagnosis. Consequently, treatment may be delayed or, in the case of a misdiagnosis, incorrect, with the risk of administering drugs that can even worsen the disease. Once the genetic defect has been identified, variable expressivity makes it harder to offer genetic counselling as the severity of the symptoms may be challenging to predict.

3 – PLEIOTROPY

Pleiotropy is the phenomenon where a gene influences multiple traits. If a mutation affects a pleiotropic gene, it may interfere with two or more biological processes (pleiotropic mutation). The mutation results in a set of seemingly unrelated symptoms that often affect two or more organs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pleiotropy: a mutation interferes with the proper functioning of multiple electronics (different organs are affected).

Pleiotropic genes are widespread in the genome. A 2017 analysis by Imperial College London estimates that 12% of protein-coding genes can cause more than one disorder when mutated [7]. What about the abundance of pleiotropic mutations in monogenic disorders?

For some clues, let’s turn to polygenic disorders, those diseases caused by multiple genes. A 2011 study estimated how often we see pleiotropy in a particular type of genetic mutation [8], SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms [9]). The researchers calculated that 4.6% of all SNPs are pleiotropic. As the divide between diseases caused by one or many genes narrows (I will discuss this point in a new post), these findings seem to suggest that the frequency of pleiotropic mutations in monogenic disorders is not negligible.

Pleiotropy complicates the diagnostic process because it may cause a disease to present with symptoms that are atypical or that overlap with other disorders. Genetic counselling also comes with challenges, as pleiotropy makes harder to predict which organs will be affected as the disorder progresses. In addition, treatment may become puzzling as well, because a medication may have different effects on the different symptoms. Finally, developing a new drug becomes particularly complex, as researchers must account for the varied and often unpredictable manifestations of the disorder.

A DAUNTING SCENARIO: COMBINED COMPLEXITIES

Individually, incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity and pleiotropy can make the effects of a single harmful mutation hard to predict, or treat. But it gets even worse: these genetic mechanisms often combine and overlap!

Among carriers of a mutation, some get sick and other not (incomplete penetrance). Among those ill, the severity of symptoms can vary (variable expressivity) and can affect different organs (pleiotropy). To complicate things even further, these mechanisms are in action in each individual: one organ might be severely affected while another mildly, or not at all. Indeed, non-penetrance (that is, absence of the illness) is a case of expressivity equal to zero.

Monogenic disorders are already rare, and incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity and pleiotropy makes them even more unique–every patient may show a different combination of symptoms and severity. This complexity may be daunting, and yet it may offer us new hopes…

FROM COMPLEXITY, NEW HOPES…

Although these genetic mechanisms add complexity to the diagnosis, counselling and treatment of monogenic disorders, they may actually guide the development of novel and more effective therapies. Here’s how:

- Incomplete penetrance indicates that a harmful mutation doesn’t always cause a disease. By identifying which factors keep some carriers stay healthy, we may enhance these protective mechanisms to prevent the disease;

- Variable expressivity shows that the severity of a disease can be modified. By revealing the genetic elements responsible for milder symptoms, we may develop therapies to alleviate the disease;

- Pleiotropic mutations cause a variety of symptoms because they disrupt mechanisms that are common across multiple biological processes. By discovering these shared mechanisms, we may design drugs that address the full range of symptoms of a disease.

In summary, incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity and pleiotropy in monogenic disorders underscore the intricate and nuanced nature of genetics. However, we can harness these complexities, much like a judoka uses the opponent’s momentum, to improve the life of the hundreds of millions living with a rare disease.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- Nguengang Wakap et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0508-0.

- Different areas of the world have slightly different definitions of “rare disease”: to be classified as rare, a disease must affect fewer than 1 person out of 2000 in EU and UK, 1 out of 5,000 in the USA, and 1 out of 1,500 in Japan.

- In a dark night, you can see around 2,000 stars according to Cool Cosmos, a NASA education and outreach website.

- Gene Map and Statistics (updated December 23, 2024), OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man)

- Around 300 million people live with a rare disease, according to The Lancet Global Health.

- Boussaroque A et al. Penetrance is a critical parameter for assessing the disease liability of CFTR variants. J Cyst Fibros. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.03.019.

- Ittisoponpisan S et al. Landscape of Pleiotropic Proteins Causing Human Disease: Structural and System Biology Insights. Hum Mutat. 2017. doi: 10.1002/humu.23155.

- Sivakumaran S. Abundant pleiotropy in human complex diseases and traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.004.

- A change in a single nucleotide common to at least 1% of the population.

Leave a reply to Ten Genomics Reads for My 2025 – DecodinGenomics Cancel reply