Search for examples of exceeding the expectations and you’ll find the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) at the top of the list.

Born in the early ‘80s as a rapid diagnostic tool for sickle cell anemia — it first appeared in Science in December 1985 — the PCR rapidly became the workhorse of molecular biology and the foundation of next-generation sequencing.

[This is Episode 4 of A Chronicle of DNA Sequencing through 5 anniversaries (1965-1995), Click me for an overview of the series]

BACKGROUND: AN OLD IDEA WITH A NEW TWIST

At the heart of PCR lies a simple idea: the DNA polymerase will add new nucleotides (elongation) to a single DNA strand (primer) once the primer anneals to a longer filament that serves as template. This idea was far from a new one.

Sanger and Coulson had already developed a sequencing method using the elongation of shorter DNA molecules in 1975. This was the “plus/minus” method, which I covered in Episode 3 of this series. The discovery of the DNA polymerase itself dates back even further, to the mid 1950s [1]!

Technically, the PCR could have been invented much earlier, and yet the stroke of genius occurred to the biochemist Kary Banks Mullis first. And even if the first version of this technique went initially unnoticed and was highly impractical, it eventually ushered a revolution…

MILESTONE: A (FOR NOW) CLUNCKY PHOTOCOPIER FOR DNA

At the tail end of 1985, the Cetus Corporation described a faster, more sensitive method to detect the genetic defect causing sickle cell anemia [2]. The method hinged on a new technology, the PCR, that Mullis had devised on a lonely night drive in 1983. The PCR acted as a true DNA photocopier, capable to rapidly make billions of copies out of a few DNA molecules.

The PCR was as simple and elegant in theory as convoluted to carry out in practice. Three technical aspects made running the first PCRs a technical nightmare [2, 3]:

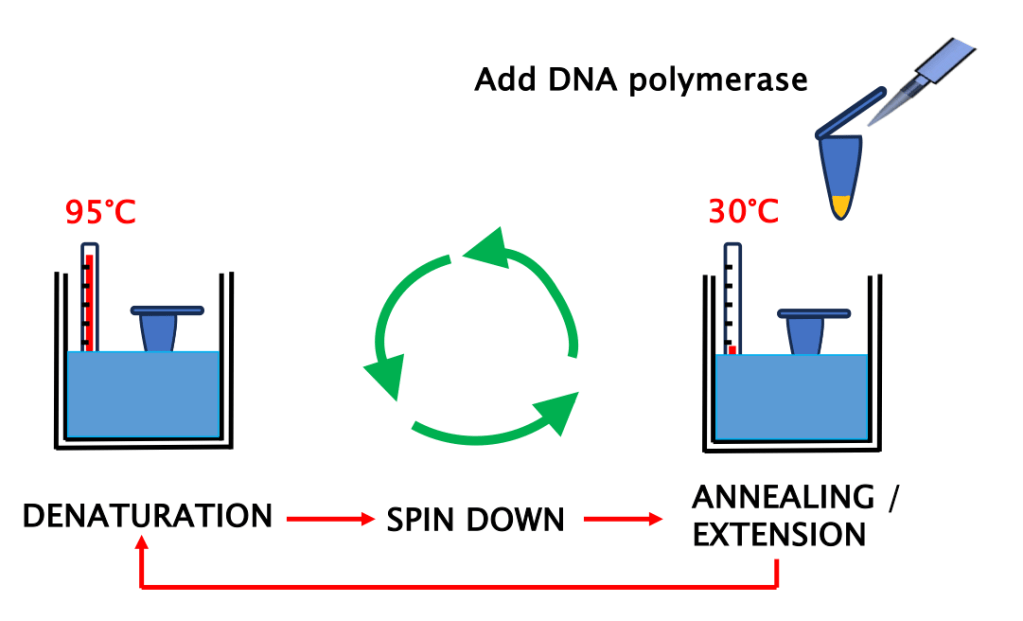

- Zero automation: Scientists used water baths to control the temperature of each step of the reaction (Figure 1). This required cyclically shuffling the PCR tubes between two baths (the first PCR workflow had only two steps: “denaturation” and “annealing” + “elongation”, Figure 2) every few minutes for an hour and longer!

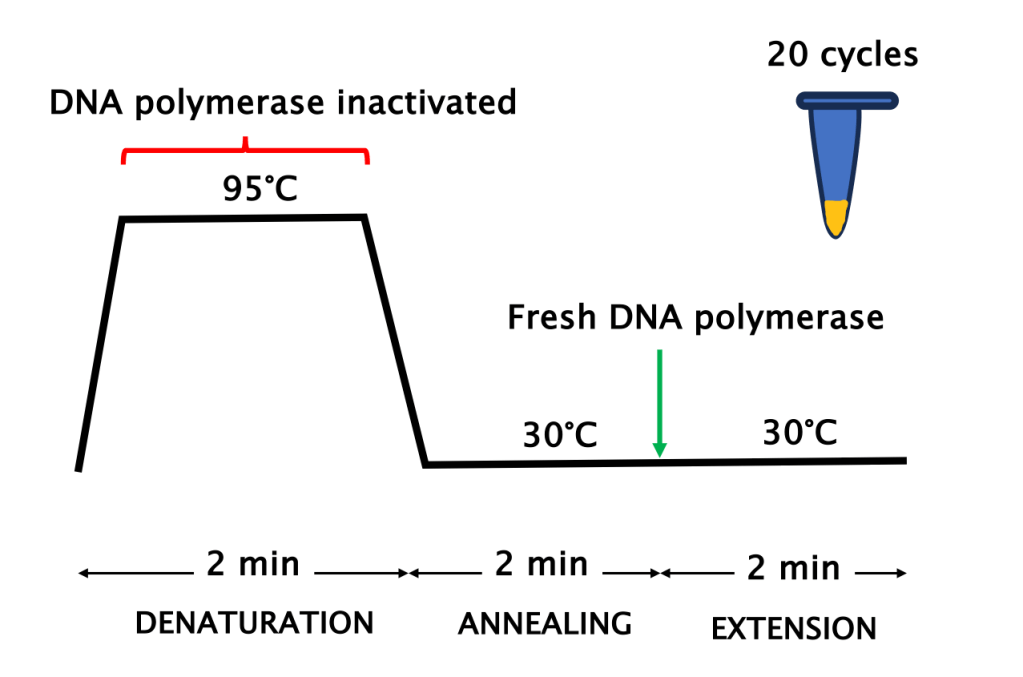

- Enzyme inactivation: The high temperature required to denature the DNA would inactivate the DNA polymerase, which wasn’t heat-resistant (Mullis used the one from Escherichia coli). As such, fresh enzyme had to be supplemented after every incubation at 95°C (Figure 2).

- Condensation alert: Besides “killing” the enzyme, the high-heat steps caused massive condensation on the tube lids. Experimenters had to briefly centrifuge the tubes after every “denaturation step” to collect the reaction at the bottom. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The first PCRs, a cycle between water baths

Figure 2: Every PCR cycle needs fresh DNA polymerase

In short, running a PCR in 1985 was tedious, laborious, prone to errors and to contamination. These technical hoops and, paradoxically, the simplicity and power of the technique (many experts must have thought that it was too good to be true) resulted in the PCR going largely ignored when it first appeared. And yet, it would have soon taken the life science world by storm.

AFTERMATH

Despite the initial struggles, the PCR was on its way to success by the late eighties – Mullis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 – thanks to three key innovations:

- The thermal cycler: machines to automate temperature changes were soon introduced. The first PCR machine, the TC1 DNA thermal cycler by Perkin Elmer Cetus, became commercially available in 1987 (Figure 3).

- The Taq Polymerase: This enzyme, from the extremophile Thermus aquaticus, replaced the E. coli DNA polymerase in 1988 (Saiki et al, 1988). As the Taq tolerated high temperatures (it is thermostable), it would remain functional throughout a PCR run, eliminating the need to add fresh enzyme at every cycle.

- Heated lids: later PCR machines kept the lids warmer than the reaction mixture, preventing condensation and evaporation. With the evaporation sorted, centrifugation spins became a thing of the past.

Figure 3: TC1 DNA thermal cycler by Perkin Elmer Cetus,

These technical advances transformed a laborious technology into a global standard that no molecular lab can avoid mastering. And they propelled DNA sequencing into the future—a future that we are still living for the most part. Among PCR’s main contributions to sequencing:

- Sequencing of tiny amounts of DNA: PCR enabled researchers to sequence DNA samples that were far too scarce for direct analysis. Before Mullis’s invention, scientists had to clone DNA fragments into bacteria, culture them to amplify the DNA, and then extract it. This process would take weeks, the PCR turned it to a few hours

- Targeted sequencing: PCR allowed scientists to “zoom in” on a specific gene or region of interest, instead of having to possibly sequence an entire genome.

- Library preparation: In modern high-throughput sequencing, PCR plays a crucial role in preparing DNA “libraries” (collections of fragments from the same DNA source). PCR allows researchers to tag each library with a unique barcode so that they can be easily distinguished when they are sequenced together (parallel sequencing).

- Bridge PCR: one of most ingenious application of the PCR came with Illumina’s “bridge amplification” technique, which revolutionized next-generation sequencing – and that will be featured in a future article on this blog…

And since this instalment has projected us into the future, the next and final episode will bring us to 1995 to witness the the dawn of genomics!

Want to learn more? Please, subscribe to my blog so you won’t miss the next instalment of this series!

REFERENCES

- Bessman et al (1956). Enzymic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1956 Jul;21(1):197-8.

- Saiki et al (1985). Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Dec 20;230(4732):1350-4.

- Mullis et al (1986). Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1986;51 Pt 1:263–73.

- Saiki et al (1988). Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988 Jan 29;239(4839):487–91.

Leave a comment