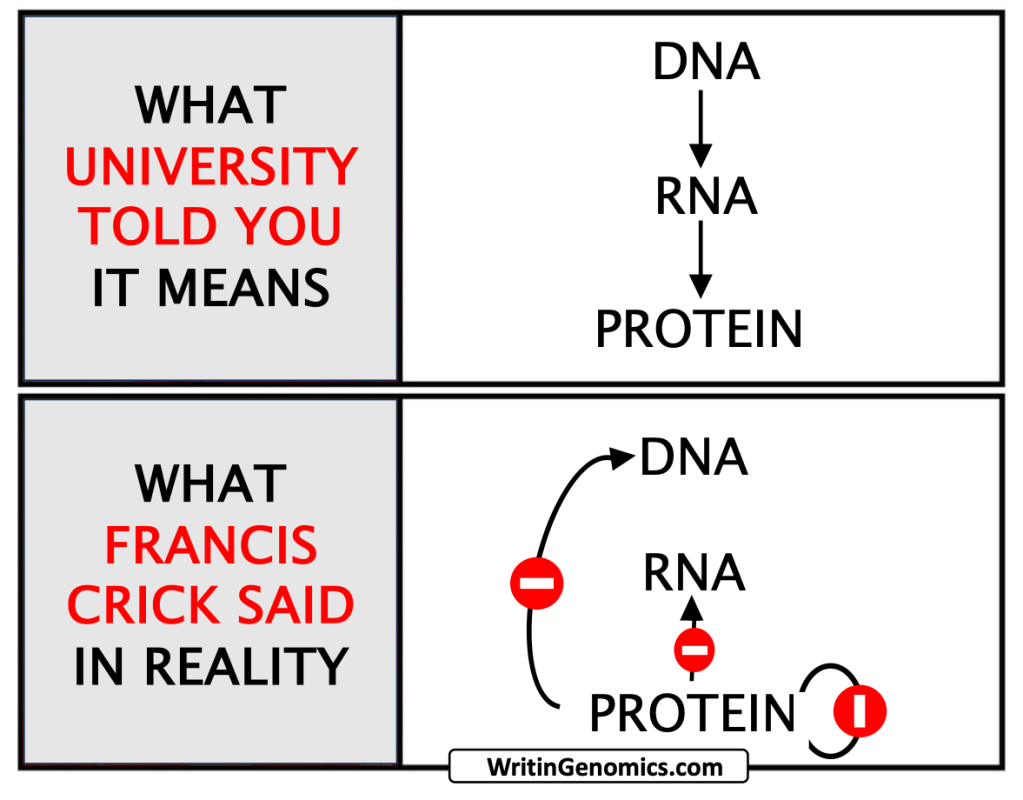

Like many of you, I believed I knew the Central Dogma of molecular biology: DNA→ RNA→Protein. I was wrong. Somewhat shocked, I learned what it really means only last week, after digging in a paper older than my dad – I am a sucker for the history of science…

Funnily enough, textbooks are probably responsible for spreading the misconception about the Dogma. A very influential manual is the major culprit: the 1965 “The Molecular Biology of the Gene” [1]. Even more ironic, its author was James Watson, friend and colleague of the creator of the Central Dogma, Francis Crick.

NOTE: this is the third instalment in my series Common Misconceptions in Genomics. I have already discussed the difference between similarity and homology (episode 1) and why not all exons code for a proteins (episode 2).

THE ORIGIN OF THE CENTRAL DOGMA

Crick enunciated the Central Dogma in a lecture at the University College of London, in 1957. No transcript is left, but Crick expanded on that talk in a 13-page article that he published a year later [2]. In both instances, he reflected on protein synthesis, making some predictions as bold (for the limited knowledge of his time) as accurate. The Central Dogma of molecular biology is one of them. Yes, his idea was a speculation, not a certainty. As Crick himself later admitted, he believed that the term “dogma” meant something totally different [1].

THE MEANING OF THE CENTRAL DOGMA

So, what does the Central Dogma actually state? Let’s unpack it.

In Crick’s own words [2], it states that

…once ‘information’ has passed into protein it cannot get out again.

I can think of three equivalent ways to look at this statement (and at the figure below)

- Cells cannot use the sequence of a protein (the ‘information’) to assemble nucleotides or amino acids in an equivalent order.

- A protein never serves as a template to make a new DNA, RNA or protein.

- The transition from nucleic acid to protein is irreversible.

In a 1970 article in Nature [3], he walked us through his logic: the translation machinery is likely too complicated to work backwards and a highly complex alternative apparatus for back-translation is improbable and unnecessary.

Again, Crick’s argument was just a speculation (“likely”, “improbable”, “unnecessary”), and yet, his bold reasoning led to a principle of molecular biology that remains unchallenged to this day.

BONUS: VIOLATIONS OF THE DOGMA?

Some have argued that two biological phenomena – reverse transcription and prion propagation – violate the Central Dogma, which is therefore not a true dogma. These arguments misunderstand Crick’s idea. This is why:

- Reverse transcription: the Central Dogma does not prohibit the transfer of information from RNA to DNA, therefore this cannot be a violation;

- Prion propagation: pathogenic prions “replicate” by causing the misfolding of pre-existing physiological prions. Crick’s principle concerns the sequence of a protein, DNA and RNA, not their 3D structure. For prions to violate the dogma, they would need to direct the synthesis of a new protein, with a specific sequence based on their own. This is not the case and therefore this cannot be a violation either.

REFERENCES

- Cobb M. 60 years ago, Francis Crick changed the logic of biology. PLoS Biol. 2017 Sep 18;15(9):e2003243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003243.

- Crick F. On protein synthesis. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1958;12:138-63.

- Crick F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature. 1970 Aug 8;227(5258):561-3. doi: 10.1038/227561a0.

Leave a comment